If you’re a heavy user of generative ai such as ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, or similar, this might have happened to you, too. I’ll use ChatGPT as placeholder for all of these, because they all do the same thing, sometimes.

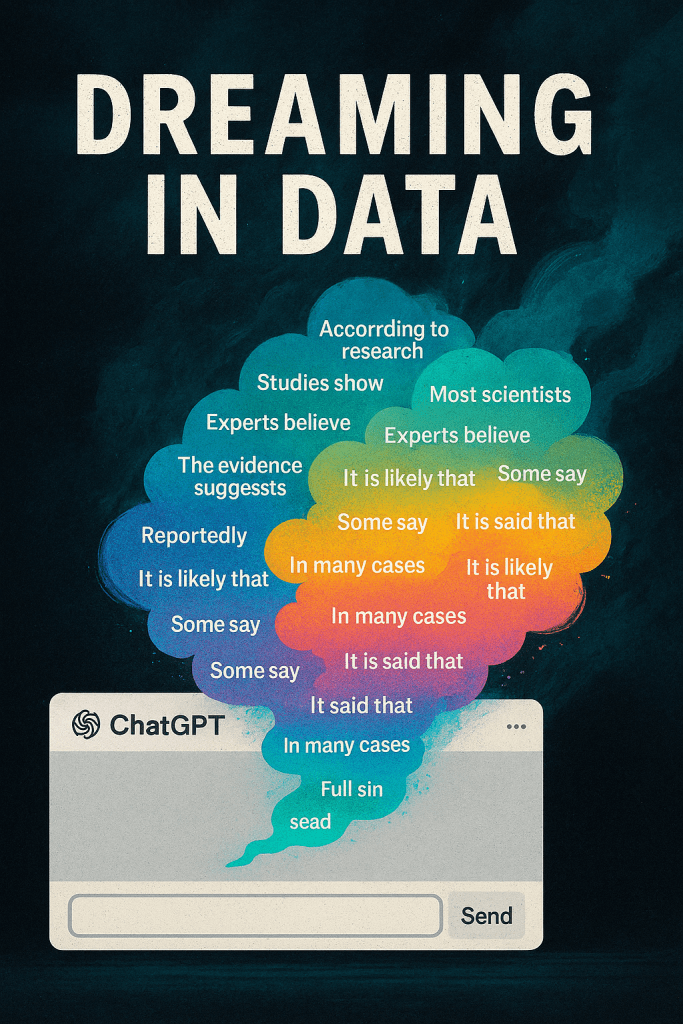

When ChatGPT starts dreaming, it doesn’t count sheep. It starts inventing facts with the confidence of a politician on live TV.

We call it “hallucination,” which sounds almost romantic, doesn’t it? Like the machine has suddenly developed imagination. In reality, it’s a fancy way of saying your AI just made something up and delivered it with perfect grammar and an air of authority. It’s not lying. It’s just doing what it was trained to do: predict the next word in a sequence that feels right. It doesn’t know the truth; it just knows what sounds like it.

That’s the catch. ChatGPT doesn’t think in facts or memories. It thinks in probabilities. When it gets something wrong, it’s not confused or malicious. It’s improvising. It’s jazzing its way through a data gap. Ask it about the first person to install Linux on a toaster and it might name a plausible-sounding geek from Finland, complete with a made-up quote. It doesn’t mean to mislead you. It just hates silence.

And we’re partly to blame. We’ve built these models to be smooth, helpful, and confident. We praise the eloquent answer over the honest shrug. We expect our digital oracle to know. But we never really taught it how to say “I’m not sure.” So it does what people do when they’re afraid to look stupid. It fakes it.

That’s why you sometimes get these beautifully written answers that fall apart on contact with reality. The AI isn’t failing; it’s performing. It’s trying to make sense of your question the way a human might in a bar conversation after two drinks, full of conviction, light on evidence.

The truth is, every time you talk to ChatGPT, you’re not tapping into a library. You’re watching a probability engine spin words into meaning. It’s a brilliant illusion, but an illusion all the same. The responsible way to use it is to know when the illusion ends. To double-check. To ask for sources. To remind it that not knowing is better than confidently hallucinating.

Because here’s the kicker. Hallucinations aren’t a bug; they’re a mirror. They show us what happens when machines try to mimic human creativity without the guardrails of human experience. They dream, but they don’t wake up.

The challenge ahead isn’t to stop AI from dreaming. It’s to make sure that when it does, it can tell the difference between imagination and information. Until then, treat every perfect answer with a small pinch of salt, and maybe a smirk.

Lämna en kommentar